Getting Real: Expectations for Corporate Cash Contributions to the Arts

By NCAR Director Zannie Voss and Rebecca Wood

How many discussions have occurred in arts organizations’ board rooms bemoaning a lack of corporate support? When we think about growth and sources of contributions, it is easy to imagine that a largely untapped panacea exists in the resources possessed by businesses. If they knew us, they would love us and they would want to support the remarkable impact we have on the community, right?

There are many outstanding stories of businesses supporting the arts. Annually, AFTA’s Business Committee for the Arts (BCA) recognizes 10 businesses from across the country, the BCA 10, which demonstrate exceptional involvement with the arts. In our home town of Dallas, the Mayor’s Office and Business Council for the Arts have teamed up to create the Mayor’s Business/Arts Initiative, which calls upon the business leaders of Dallas to cultivate the arts community.

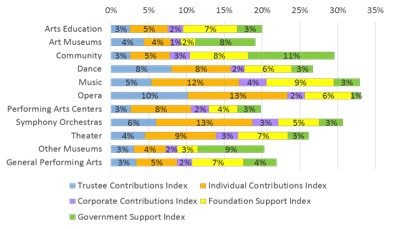

Yet the data tell us there are limits on what to expect. Despite the many examples that speak to the important and meaningful ties between businesses and the arts, corporate arts support should be understood in context. According to the data, if your organization’s annual cash contributions from corporations support 2% of your total expenses (reflecting only cash donated in the current year for the current year’s activities[i]), your organization is at the national average. This compares with an overall average of 3% of total expenses supported by trustee contributions, 5% by contributions from other individuals (non-trustees), 7% by foundation support, and 3% by support from all levels of government combined. As shown in the Figure, there is a good deal of variation in these percentages across arts and cultural sector for most of the sources of contributions. However, corporate cash support maxes out at an average of 4% of total expenses for organizations in all sectors:

Figure: Level of Total Expenses Supported by Annual Cash Contributions, by Sector and Source, 2014

Expecting cash, corporate support to cover 1% to 4% of budget -- depending on the arts and cultural sector -- is realistic. This is the normal range for all organizations regardless of budget size, and it has remained at virtually the same level over the past 5 years. Expecting corporate support to cover more than 1% to 4% of budget will require exceptional efforts, relationships, and local businesses.

So what’s the hold up? Why are corporate cash contributions not a greater source of arts philanthropy? For answers, we examine the issue from a business’ perspective by turning to the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the tensions that it reveals. There are a myriad of CSR definitions, behaviors, and justifications. They tend to cluster around two schools of thought[ii] both captured well by The Dallas Mayor’s Business/Arts Initiative in its statement, “This initiative should not only be considered as a business opportunity, but also as a cultural investment in the city and its people.” In other words, it’s good for the community and it’s good for business.

Most corporations have one, looming question in mind when it comes to charitable contributions: does it pay to do good? Moral imperatives and soft credit aside, management’s first priority is to maximize shareholder value. All else being equal, customers should be more inclined to give their business to a company that they perceive to be munificent and corporate philanthropy can be a source of differentiation. However, several studies have found that firms that participate in philanthropic giving have basically the same rate of profit as those that do not, so if philanthropy does not enhance profits, why engage in the activity?

From the vantage point of many firms, there is not a clear, straight line that connects engagement in CSR activities and positive outcomes, either financial or reputational. It is fraught with pitfalls. Some critics hold that firms should only participate in profit maximizing activities, and to do otherwise is to give away other people’s money.[iii] Others take issue with the firm’s focus of philanthropic giving. And, even if a corporation can escape these criticisms and determine the optimal level of CSR to engage in through cost-benefit analysis[iv], there is always the risk that: 1) their customers are not even aware of their philanthropic efforts and, if they are, 2) that consumers may come away with negative impressions of corporate self-promotion,[v] self-interest, and exploitation[vi] if the CSR activities are not carefully managed.

According to AFTA’s The BCA Report: 2013, the top four reasons why businesses that support the arts do so are that they believe the arts improve quality of life in the community, help create a vibrant community and society, improve academic performance for students, and offer education initiatives that benefit the community. They see the arts as an agent for positive social change. These are the corporations that get arts organizations to the 2% corporate contributions index average. The BCA Report: 2013 (p. 9) reveals that roughly the same percentage of businesses perceive supporting the arts to be either a high/top priority as the percentage that view it as a fairly low or very low priority (27% and 28%, respectively). When businesses that do not support the arts are asked why, their top reason is budget constraints/not enough revenue (35%), followed closely by other priorities: social causes such as education, healthcare, or other social causes take precedence (30%). While the arts provide social impact in the community, they compete with these other nonprofit sectors for limited business attention.

We owe a debt of gratitude to the exceptional businesses that see the arts as both good for business and good for the community. Corporations play an important role in the arts and culture ecosystem, just as arts and cultural organizations play a vital role in their communities.

By not engaging in CSR or choosing to prioritize other social causes, corporations are perhaps not living up to our expectations, but neither are they in existence to do so. We aren’t advocating that arts organizations put it in park and give up on developing business support. If increased corporate support is a goal, however, it will take exceptional efforts and a sea-change in most corporations’ perceptions of the value of the arts in and on society. Until then, we should recognize what is the current norm and why it is where it is.

[i] It would be reasonable to argue that inclusion of non-cash contributions of materials, services and facilities from businesses would boost that 2% to a greater extent than would non-cash contributions from the other giving sources since businesses disproportionally have non-cash resources to offer arts organizations. Including in-kind corporate giving would raise the 2% to roughly 2.5%; however, we focus here solely on cash contributions across all sources. Relatedly, we do not include earned revenue from corporate sponsorship as this activity represents a fee for service.

[ii] Bénabou, Roland and Jean Tirole (2010), "Individual and Corporate Social Responsibility." Social Science Research

[iii] E.g., Friedman, Milton (1970), “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” New York Times Magazine, September, 13.

[iv] McWilliams, Abagail, Donald S. Siegel, and Patrick M. Wright (2006), "Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategic Implications," Journal of Management Studies, 43 (1): 1-18.

[v] Pomering, Alan, Lester W. Johnson, and Gary Noble. "Advertising Corporate Social Responsibility." Corporate Communications: An International Journal. 18.2 (2013): 249-63. Web.

[vi] Bénabou, Roland and Jean Tirole (2010), "Individual and Corporate Social Responsibility," Economica, 77, 1–19.